In 1979, a young Gay man named Jim Skeen moved to Seattle from Washington, DC, where he had worked as a volunteer at a clinic that tested and treated men for sexually transmitted diseases (venereal diseases, or VD, which was the term used in those days). He had hoped to volunteer at such a clinic in Seattle, but when he asked around, he learned there was no such thing in his new city.

So he placed an ad in the Seattle Gay News, looking for people who might be interested in organizing a local Gay clinic. He called a meeting, at which several people showed up – Gay doctors, nurses, and nonmedical people who were willing to be trained as paraprofessionals to perform screening tests for gonorrhea and syphilis, two diseases that were prevalent in the local Gay male population.

Prior to this, the only options Gay men in Seattle had for such testing were the local Health Department's VD Clinic and physicians in private practice. Some were wary of using the Public Health clinic, given that homosexual behavior had only recently been decriminalized in Washington state, and the it was located downtown in the Public Safety Building, which also housed the Seattle Police Department and the city jail. Others felt that there were few physicians who were knowledgeable enough about Gay sexuality to treat Gay men with competence and respect.

This small group met regularly and figured out how to incorporate this new clinic entity, using the nonprofit umbrella of the Gay Community Social Services organization, and taking the legal title of Seattle Clinic for Venereal Health. There had been some concerns that a clinic with the word "Gay" in its title might have trouble raising funds from donors. But, except for the fiscal formalities, the clinic would be called Seattle Gay Clinic (SGC).

The early years

So, where to locate this new clinic's activities? Organizers approached the Country Doctor Clinic, which since the early '70s had operated in a firehouse, Station Seven, on the corner of 15th Avenue East and East Harrison Street on Capitol Hill. The surplus building had been turned over by the City to Country Doctor and an organization called Environmental Works.

Country Doctor agreed to let the Seattle Gay Clinic use its exam rooms and waiting area on Saturdays and Wednesday evenings. There were a few glitches that had to be ironed out, such as how to keep SGC's supplies and files separate from Country Doctor's, but a cooperative agreement was worked out.

Volunteer doctors, nurses, and lab techs trained Gay laypeople, called "screeners," to take samples from clients and to prepare the specimens for testing at the Health Department's laboratory. A system was devised whereby SGC clients could register using a coded system of numbers and letters, so that their records could remain anonymous. Clients would phone to get their test results, and would then be offered treatment and follow-up, if needed.

Within a couple of years, a cadre of about 50 volunteers had been recruited, and working in rotation, they were able to screen and test about 20 patients per half-day session.

By this time, Gay clinics had become established in several cities around the United States, and Seattle's joined the National Coalition of Gay STD Services, which published a national newsletter that allowed the clinics to share their various approaches. SGC also produced a monthly newsletter for its volunteer staff, keeping them abreast of local and national news relating to the sexual health of Gay men.

The clinic held fundraisers, including dances and bar parties, to support its operational expenses, and formed a friendly partnership with the Imperial Court of Seattle, which held drag shows to raise money for the clinic. Activities like these served to raise community awareness about the clinic and its services, and also brought new volunteers into the fold. In many cases, participation in SGC volunteer work helped people to further their coming-out process, and many gained skills that they wouldn't otherwise have had a chance to develop.

Finding doctors

Many of the men who came to the clinic for STD services didn't have regular doctors who could evaluate and follow them for other medical conditions, or provide general primary care. One of the SGC volunteers took on the project of compiling a list of physicians who would be able and willing to provide medical care for Gay men. He developed a questionnaire designed to survey local physicians and to elicit information on their readiness and preparedness to provide care in a nonjudgmental fashion, and the King County Medical Society agreed to send it out to all its members. The response was greater than expected, with over 70 doctors agreeing to take referrals. Their names, areas of specialty, and contact information were compiled and published in a booklet called "Directory of Gay-Sensitive Physicians," which was handed out to SGC clients.

The epidemic begins

At about this time, screeners at the clinic were beginning to notice that some clients were exhibiting enlarged or painful lymph nodes, a condition called lymphadenopathy. Harborview and the University of Washington had begun one of the first studies in the US on how this condition affected Gay men, and SGC staff referred clients with swollen lymph nodes to participate in it. In time, this condition would be recognized as one of the precursors to what would later become known as AIDS.

The first cases of AIDS (originally called Gay cancer, or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID)) were reported in Los Angeles and New York City in 1981. SGC volunteers followed national developments, and posted clippings and information in the clinic waiting room, often gleaned from sources such as the New York Native and bulletins from the federal Centers for Disease Control.

The first cases of AIDS in the Seattle area were reported in 1982. In December of that year, SGC volunteers organized the first public forum in Seattle about the epidemic, drawing a crowd of three hundred people to Seattle Central Community College to hear a panel discussion and Q&A session, with presentations by representatives from the Public Health Department, Harborview Medical Center, and SGC's volunteer medical director. The sign-in sheet from this event would prove valuable in the coming months as a way of contacting people to become involved in fundraising and advocating for the needs of people living with AIDS, and in organizing future events, such as another forum called "AIDS: Loving and Caring for Our Own," which featured speakers flown in from San Francisco.

The arrival of AIDS brought SGC into closer cooperation with the Seattle-King County Public Health Department, which formed an AIDS Advisory Task Force that included two SGC volunteers as members. The task force identified a need for some sort of hotline to field questions coming in from the general public and people who thought they might be at risk for this new disease. A volunteer from the clinic agreed to staff the hotline for free. Later, when funds became available from Seattle and King County, this became a paid position.

Building services for people with AIDS

Although the cause of AIDS was still not clearly known, and there was no test to show who was infected, there was a need to provide a place where worried people could get examined in a clinical setting. Public Health and SGC volunteers came up with a model for an AIDS Assessment Clinic, to be staffed by a nurse practitioner. A proposal for funding was presented to the Seattle City Council.

A demonstration and mass march was scheduled by the Seattle Gay Clinic, Seattle Counseling Services, and the Dorian Society, timed to coincide with the City Council hearing. A rally was held at Westlake Center, and over a thousand people marched from there to City Hall, where testimony was heard from supporters of the proposal. The event garnered front-page headline coverage in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, with a photo of the marchers.

The City agreed to provide start-up funding for the AIDS Assessment Clinic and the AIDS Information Hotline. Two weeks later, the King County Council agreed to provide additional funding for the startup program, which, over the years, evolved into the AIDS Prevention Project, later known as the Public Health Department's HIV/AIDS Program. Former SGC volunteers served as that program's initial medical director and administrative manager.

Chicken Soup Brigade

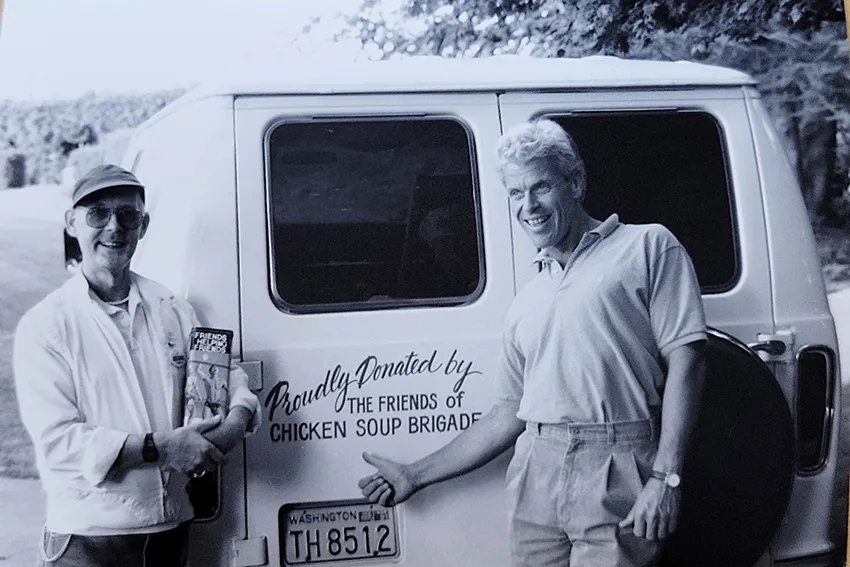

The clinic volunteers had formed several committees to take care of various tasks. The Outreach Committee met in December of 1982 to discuss ways the clinic could connect with and help people who were becoming ill (whether with AIDS or other disabling conditions). A proposal was launched to form a "buddy network," similar to one that had been organized in New York by the Gay Men's Health Crisis. SGC's equivalent was dubbed the Chicken Soup Brigade, with the intention of providing practical support – transportation to doctor's appointments, help with grocery shopping, preparing meals, housecleaning, etc. – for Gay men who were unable to get around on their own and who did not have family members or partners who could help them. Local physicians were encouraged to call on the Brigade if they had patients who needed help.

At first, there was just a trickle of referrals, but soon a substantial number of requests for help were coming in, and the small crew of Brigade volunteers expanded. The Brigade was featured in a PBS TV documentary called Diagnosis: AIDS, which was aired nationally.

Eventually a special volunteer coordinator was needed to handle requests and logistics. In 1986, the clinic decided to hire a full-time, paid coordinator. As the Brigade grew, it split off from the clinic and formed its own nonprofit entity. The focus shifted from providing a variety of supportive services to preparing and delivering meals, and, over the years, the Brigade's mission expanded from serving people with AIDS to include others with disabling conditions. Now the Chicken Soup Brigade is a multimillion-dollar enterprise, with a large warehouse-size kitchen operation, located in Georgetown, that serves hundreds of shut-in clients in the Seattle area.

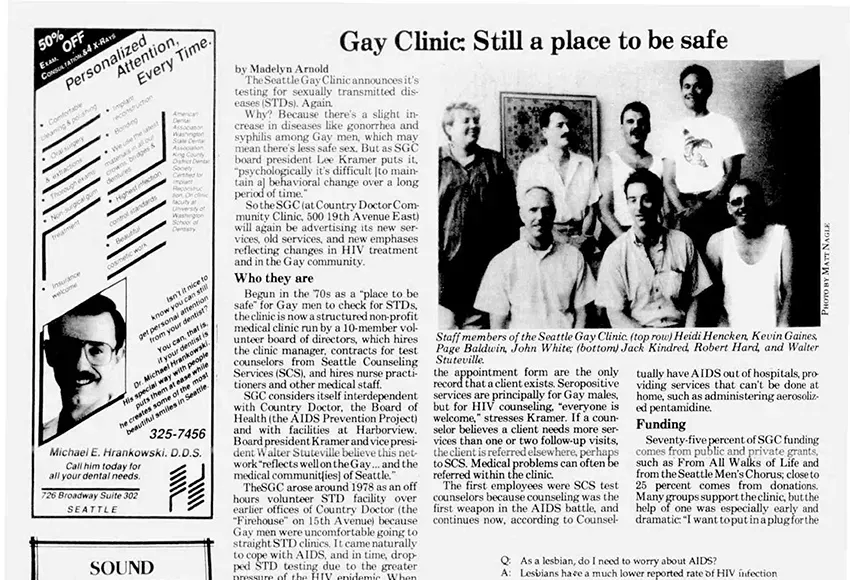

In 1984, the virus that causes AIDS was isolated. Originally called HTLV-III, it became known as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). By 1985, a test was developed to identify HIV in the bloodstream, and Seattle became one of the first cities in the US to pilot this test. The Health Department contracted with Seattle Gay Clinic to provide counseling and HIV testing for Gay men. By then, Country Doctor had moved its clinic from the 15th Avenue firehouse to a new clinic on 19th and Republican, and Seattle Gay Clinic moved with it.

Founding other agencies

During the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, Seattle Gay Clinic volunteers were instrumental in organizing several nonprofit agencies that provided services beyond what traditional public health programs could deliver. In 1983, the Northwest AIDS Foundation (NWAF) came into being, originally with a mission to help coordinate interagency AIDS education and care efforts, and to raise funds for the needs of people with AIDS. NWAF's first board president was a Country Doctor physician who also had served as volunteer medical director for Seattle Gay Clinic. Over time, the NWAF grew its mission to include case management services and multimedia AIDS education programs targeting the general population and people at risk for HIV/AIDS infection. In 2001, the NWAF merged with the Chicken Soup Brigade and became Lifelong AIDS Alliance, allowing for administrative savings and enhanced fundraising capabilities.

Seattle Gay Clinic volunteers also were key movers in forming the organization Shanti Seattle. Based on a model created in San Francisco, the program provided emotional support for people living with AIDS and their families, partners, and caregivers. SGC paid for four volunteers to go to San Francisco for training, and those volunteers came back and formed a large network of emotional-support volunteers.

At about the same time, SGC volunteers participated in forming the Seattle AIDS Support Group, which facilitated group meetings of people living with AIDS and/or HIV. That organization filled the rooms of a large Capitol Hill mansion called Dunshee House with support groups and educational activities, eventually including substance-abuse recovery groups in its menu of services. It currently operates as part of the organization Peer Seattle.

Legacy

Seattle Gay Clinic continued to provide services until 2004, when its board decided to dissolve and end its activities. The Health Department then began contracting with Gay City Health Project (now called Seattle's LGBTQ Community Center), which carries on the tradition of providing free or low-cost services in a community-based setting.

So, from simple, grassroots beginnings in 1979, the Seattle Gay Clinic went on to establish itself as a peer to other Gay-run clinics across the country, rose to the unanticipated challenge of responding to the AIDS epidemic, formed significant partnerships with Public Health of Seattle & King County, and seeded several other vital organizations in the Seattle area.

Unfortunately, many of the SGC volunteers who spearheaded these efforts died during the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. But their spirits live on in the legacy of activities that have helped to make Seattle a safer and healthier place for LGBTQ+ people to live their lives.