In late July, an escalated Twitter feud between two Christian musicians led to a drag queen topping the iTunes Christian charts. The debacle started with a snarky comment by Sean Feucht, a conservative Christian musician and failed GOP congressional candidate, who tweeted his disapproval of a collaboration between Derek Webb, frontman for contemporary Christian band Caedmon's Call, and drag queen Flamy Grant.

In true culture war fashion, Feucht referred to the collaboration as a sign that "these are truly the last days," and as one thing led to another, backlash against Feucht's tweet caused Grant to surge in streams and downloads.

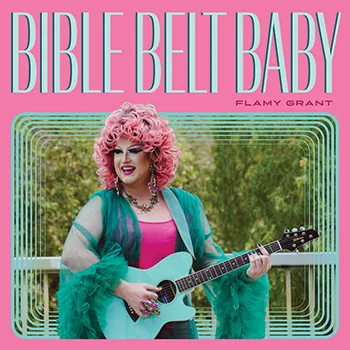

The collaboration, the single "Good Day" from Grant's 2022 album Bible Belt Baby, is an upbeat declaration of an unbreakable spirit in the face of rejection. In the middle of this Twitter tiff and its opportune outcome for Grant, the experiences of Queer people in evangelical Christianity have found a unique if unlikely voice: a campy, gospel-singing, gospel-preaching drag queen.

Grant's Vision

Flamy Grant is the stage name of San Diego-based Matthew Blake, a former worship leader raised in Appalachia. Blake created Flamy Grant during the COVID-19 pandemic as a way of keeping his own sanity. But as she recounts to Paste Magazine, when her pastor asked her to give a sermon in drag, the TikTok videos she made to practice went viral, racking up nearly a million views.

In an article with Newsweek, Grant explains her religious background. "The evangelical faith I was raised in is, sadly, founded entirely on fear and buried in shame. I believe in the power of love to cast out fear." She speaks of loving Christian music as a kid, saying in a tweet that this surge is having "such a massive impact for hurting, closeted kids in churches. I know because I was one."

Blake has run the Heathen Podcast since 2017, since well before he created Flamy Grant, and on its website, Flamy describes herself as "an apostate, a heretic, [and] a heathen – and I've never felt more whole." Her return to Christian music as Flamy Grant comes in the wake of what she calls a process of "deconstructing" faith – undertaking critical analysis of its roots. In Paste, Blake explains, "I have a lot of personal spiritual practices, but it's really hard to identify with the Christian church in America right now." His goal in his music is to help "kids to see that there's options for them. That they are not alone."

Grant's Music

Flamy Grant's style in her 2022 album Bible Belt Baby draws heavily on such influences as folk, Americana, and gospel. Her lyrics unfold couplet by couplet over lilting guitar, evoking in some tracks the tranquility of Alison Krauss and Sarah Jarosz, and in others the bold effusiveness of Winona Judd and CeCe Winans. Her lyrics at times present as ham-fisted, and her sound derivative, but, understood as a blend of sincerity and camp, she makes an undeniable impact.

If Bible Belt Baby contains a throughline, it's Grant's affirmation that shame does not have the last word as Queer people seek home. Home is a perennial theme in the musical traditions to which she pays homage, and she uses her experience as a Gay Christian to frame home as both a crisis and a promise.

Her drag utilizes nostalgia, not in the usual sense of evoking times gone by, but as a corrective to a demographic shaped deeply by being denied a past of their own. Home is both the wound of the past and a hope for the future.

Grant's music encompasses several themes well known by Queer people who fight for their existence in Christian spaces. Her opening track, "What Did You Drag Me Into?," recounts growing up Queer in a Christian household, at one point discovered in youthful drag and seen as "something shocking and obscene," at another point playing the Virgin Mary in drag at a church nativity pageant while a big gospel chorus flies overhead.

She sings the praises of the Bible's strong women in "Esther, Ruth, and Rahab": "in those pages you'll find badass rebel warriors and queens, / Prophetesses, witches, whores, and wives all causing scenes," and she wrestles with the dark night of the soul in "Holy Ground:" "What silence must it take / To soothe so deep an ache? / I would let the water take me down / If I were not afraid to drown."

Grant places herself in a musical tradition rife with expressions that make ready fodder for drag, as exemplified by Trixie Mattel's Two Birds and the aesthetics of Dolly Parton. She meets her own namesake head-on with a cover of Amy Grant's 1997 crossover hit "Takes a Little Time," spinning it with a soothing American Midwest idiom sure to elicit feelings of home to those who grew up amid floral upholstery and wood paneled living rooms.

Grant's significance

Neither Grant's style nor her experiences are universal. Bible Belt Baby is not for everyone, instead playing to a specific, even if widespread, cultural experience. Yet the wider cultural relevance of the moment that thrust Grant into the limelight affects us all. Her music, her style, and her art, when understood in the culture war context, make her a notable phenomenon. Her art is more than nostalgia, more than camp, and even more than drag. Her art is medicine.

And for far-right culture warriors who decry her message as a sign of "the last days," one can only hope that they are right, and that the days of shame, fear, and hate are coming to an end.