When I was first diagnosed with AIDS, I was terrified. I felt ashamed. I felt despair. But above all, I felt alone.

I had just been experiencing homelessness, with a rescinded job offer due to the last recession, and without a family or other social support system due to coming out as Gay. As a Black man from a Nigerian background, the pain was compounded when I experienced harassment or even cold indifference to my situation due to racism and oppressive systems.

My life sentence for existing in these intersections of my identity suddenly felt like a death sentence.

It took months, and even years, to come to a place where I could finally feel healthy again. Through the kindness of nonprofit organizations and newfound friends, I was slowly but surely placed on the path to recovery. I started a regimen of antiretroviral drugs that brought me from the brink of death back to just HIV-positive, until finally I was able to get the virus under control to the point where it is no longer transmissible.

I was also able to find steady housing, and employment that could keep me fed, housed, and able to afford lifesaving medical help.

To this day, I still feel guilty that I can access a doctor when I need care. I still wonder if I'm "undeserving" of the nice apartment near the park, after knowing what it felt like to make do on others' couches or take a risk on the streets. To enjoy a sweet bubble tea – a favorite of mine – is to experience a luxury I once thought beyond me.

I know deep inside that I deserve joy, and that many of the things I continue to second-guess for myself – like safe shelter and adequate food – are human rights I deserve simply because I am alive.

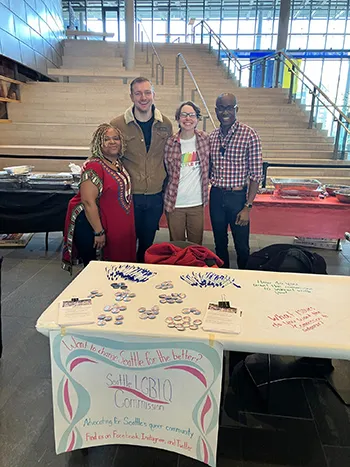

That is where joy as resistance comes in, and where paying it forward is my reconciliation. I am now working full-time in HIV advocacy, as well as serving as a board member of many local LGBTQ+ and HIV+ advocacy organizations.

I am proud of my journey, but it is one that I am taking because I don't want others to go through what I went through. The tears I shed in those darkest, loneliest moments are ones I wish for nobody.

To that end, I am disheartened that, in a city filled with such wealth, there are so many struggling to make do, without their basic human rights, such as housing, healthcare, and nutrition. Compounded with the ongoing social stigmas related to HIV status, it becomes even harder for some to seek these services.

As the second annual "HIV Is Not a Crime Day" has come and gone (February 28), I reflect on what this means for a seemingly progressive area such as Seattle. In numerous states across the country, there are overt attacks on people living with HIV and AIDS, including laws that not only further stigmatize people living with the condition but that discourage people from getting testing and seeking resources [https://www.hivisnotacrime-etaf.org/about/].

These laws may not be what we have on the books in cities like Seattle and states like Washington, but much like a lot of our area's progressive politics, often we see performative gestures taking the place of meaningful action. In short, the absence of criminalized laws does not absolve us from our moral responsibility to do better.

My work and advocacy on HIV and AIDS awareness and resources has continued to inform me of where we need to take more action as a region. Despite our city and greater metropolitan area being home to some of the most ethnically diverse neighborhoods in the nation, our infrastructure for disseminating information about HIV/AIDS is often lacking when it comes to cultural sensitivity, breaking language barriers, and physically meeting people where they are at. Our healthcare in general, especially for lower-income people – predominantly BIPOC neighborhoods and in immigrant communities – is lacking, and especially so when it comes to health conditions that are already greatly stigmatized.

I ask my siblings in the LGBTQ+ community to join me in advocating for those with similar intersections of identity that are often overlooked by our institutions. Talk with your friends and family. Demand that your local policymakers include culturally sensitive HIV information, and that neighborhood clinics prioritize HIV/AIDS treatment.

Just as we are fighting back that it's "okay to say 'Gay,'" we must also be willing to shout "HIV/AIDS" and, with that greater presence, demand more direct interventions in our communities. My goal is that in my lifetime, not one more person will have to experience what I went through to get support and treatment. We are a community that looks after each other; let's continue to stand with each other, especially when confronting stigma, so that more can stand with pride.