SGN Book Club explores LGBTQIA+ literature, new and old, from the fresh perspective of a Gen Z book enthusiast.

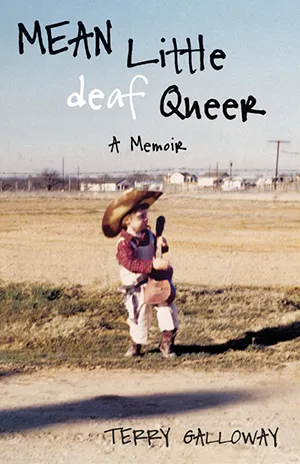

This week's SGN Book Club decided to pick up a copy of performer Terry Galloway's memoir, Mean Little Deaf Queer, a collection of stories from the author's childhood and young adult life as a deaf person, a Queer person, and, as the title might suggest, a girl with a bit of a "mean" streak. In between stories of her coming of age and coming to be, she adds old family lore, retelling classic tales of her tight-knit Texas ancestors from before she entered the picture.

Exiling community

One theme that connects Galloway's many stories from adolescence to adulthood is her attempt to form a community around her. Through an internal sense of elitism, she often rejected those who shared identities with her in order to climb the social ladder. As a child, she was a tomboy, always searching for her way into the boys' circles.

When she finally found a way to fit in with her male playmates, Galloway recalls with a tinge of shame that it was at the expense of her female peers. "Girls tended to like me." she writes. "They trusted me and my dumbstruck heart. It was a grave mistake. I might love the girls but I lusted for power." Working as a double agent, she would lure a girl away, only to watch as her group of male friends jumped out and pinned her down, forcing her to kiss them.

Through this exchange, Galloway developed a sense of her gender. She recognized a longing to be one of the boys and a feeling of jubilation when they allowed her into their circle. "When they offered me a place in line, I felt as honored, as if I'd been asked to join the Marines," she recalls. However, Galloway also made the mistake of looking into the girl victim's eyes, and what she saw was the unmistakable connection of sameness.

This story continued to play out in different ways throughout Galloway's narratives. She recounted her experiences at a summer camp for children with disabilities and her smug feeling of superiority as she watched children with physical and mental handicaps so severe that they could not leave the shallow end of the pool. Because Galloway's disability, deafness, was one she could easily hide, she felt as though she were better than the others at the camp. As a result, she isolated herself from acceptance into a greater community.

As a young adult, Galloway recognized her queerness in the attraction she had for women. However, because she was also attracted to men, she found it easier to hide her same-sex romances and masqueraded as straight when in public or around her family. In the same ways she had distanced herself from female and disabled communities, Galloway attempted to play more socially acceptable roles.

Part of her desire to "pass" for straight, able-bodied, and even male at times were her feelings of inadequacy. She felt she was not Queer enough or disabled enough to truly fit into communities that seemed to unite and celebrate those who came together due to their shared experiences.

Little-d deaf

As Galloway explains in her memoir, she was not born deaf. She was diagnosed at age nine with a rare condition that would cause her to go almost entirely deaf by her early teens. Because she was born hearing into a hearing family, her experiences with deafness differed from most of those in the deaf community.

"There is a definite hierarchy in that deaf culture," she explained. "If you are deaf – a deaf person born to a deaf parent – and your language is Sign, and the company you keep is primarily deaf, you are Deaf with a capital D," Galloway continued. As someone who had never met another deaf person, who didn't know Sign, and had at one point in her life been entirely hearing, Galloway felt she did not fit into the deaf community at all.

For most of her young adulthood, she saw her status as "little 'd' deaf" [sic] as a symbol of superiority. Excluding herself from the deaf community, she was able to pass (with some effort) as able-bodied. She did not feel a kinship or connection to the deaf community until she was much older and learned about some of the harsh realities of deaf institutes, discrimination against people who can only sign, and even children abandoned at birth for showing signs of deafness.

Throughout her stories, Galloway references a nonspecific "us" and "them." "Them" often refers to a group of oppressors, the ones who just don't get it. Despite despising "them," Galloway admits she spent most of her life trying to become them. As a child at summer camp, she saw herself as "them," and cast scorn on the disabled kids around her. As an adult, she sank into a feeling of "specialness" for "overcoming" her disability and acting on stage, just like all her able-bodied cohorts.

She bought into the narrative pushed by an ableist society that it is the responsibility of the person with a disability to overcome, and once they can operate in the same ways able-bodied folks do, they ought to be celebrated. However, those who cannot overcome should be hidden away or infantilized.

"My deafness had made me memorable, and I liked the fuss when people oohed and aahed over how much I had accomplished despite my 'terrible handicap.' I was made to feel special, a word with which I had had a long and convoluted relationship," she writes.

Galloway shifted her thinking after an encounter teaching acting workshops in Europe. Each of her fellow actors were chosen to lead a different class, based on skills or techniques they had. Galloway was assigned to teach a workshop to adults with disabilities. She saw this assignment as a slap in the face – an acknowledgment that no matter how hard she worked to leave her disability behind, the rest of the world still saw her as an outsider.

In the class, she assumed her students would be unable to carry out any of the basic acting exercises she knew. Instead, she spent the entire two hours talking with them about their lives. It wasn't until after the class ended that Galloway reflected on the opportunity she had thrown out. She realized that despite her students lacking some abilities, they also brought with them exceptional qualities she had overlooked and cast aside as worthless.

Changing the societal narrative

Despite the stories she built up in her head and the expectations she had for herself and others, Galloway learned that the world, and people around her, were capable of surprising her. In her young adult years, she started a relationship with a woman but felt too afraid to come out to her family. It was the '70s, and she feared that her father, an ex-military spy, and her mother would not approve of her sexuality.

One day, tired of her family referring to her girlfriend as her "best friend," she blurted out the truth. To her shock, both parents accepted her and came to love all the Queer friends she brought home, even going so far as to become surrogate parents for those who had been disowned by their biological ones.

After her encounter in Europe, Galloway realized that her ways of thinking about disability culture were shaped by and aiding ableist ideologies. She realized that no matter how hard she swam, she would always be in the "shallow end of the pool" if she continued to hold everyone to the same standards. She became an advocate for disability rights and accommodations and realized that making it further than others in a flawed system was not an accomplishment worth striving for.

Mean Little Deaf Queer is a story of growth, of seeing beyond one's body and the narratives society tells us about our shortcomings. It is the story of a woman coming of age and coming out. Queerness and disability are two identities that often overlap, and Galloway uses comedy and reflection to illustrate her journey to accepting and celebrating all her identities.