Hip-hop: it isn't just a music genre – it's always been more than that. It's a cultural revolution that continues to galvanize art scenes, dance, politics, fashion, and culture throughout the globe.

The hip-hop movement goes back to the 1970s in New York City, when economic and social demographics experienced a startling change. With that came an increase in poverty, crime, and gang violence. Black neighborhoods were hit the hardest, and Black youth yearned for forms of self-expression.

Hip-hop music reflected the day-to-day experiences of youth living through these harsh conditions. Block parties were where some of the earliest forms of the genre were developed, and photographers were on the scene to document it all. These photographs – which created instant icons – cannot be separated from what the music relays: individuality and self-expression, political rhetoric and empowerment.

MoPOP's "Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop" exhibit explores the evolution of this music, from the time when no one knew how long it would stick around, until the present day. The exhibit is based on curator Vikki Tobak's book Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop, and Fab 5 Freddy contributed to it by taking on the role of creative director.

The album that got me heavily involved in the hip-hop genre was The Roots' Undun. My older brother sent me a few songs in college, and I became instantly hooked. I wasn't new to this kind of music, but this album hit me differently. It tells the story of a fictional Philadelphian, Redford Stephens, who becomes entangled in the drug trade and meets an inevitable but early downfall. "This is poetry," I thought to myself as I found my head and body grooving along with the lyrics and heavy drumbeats.

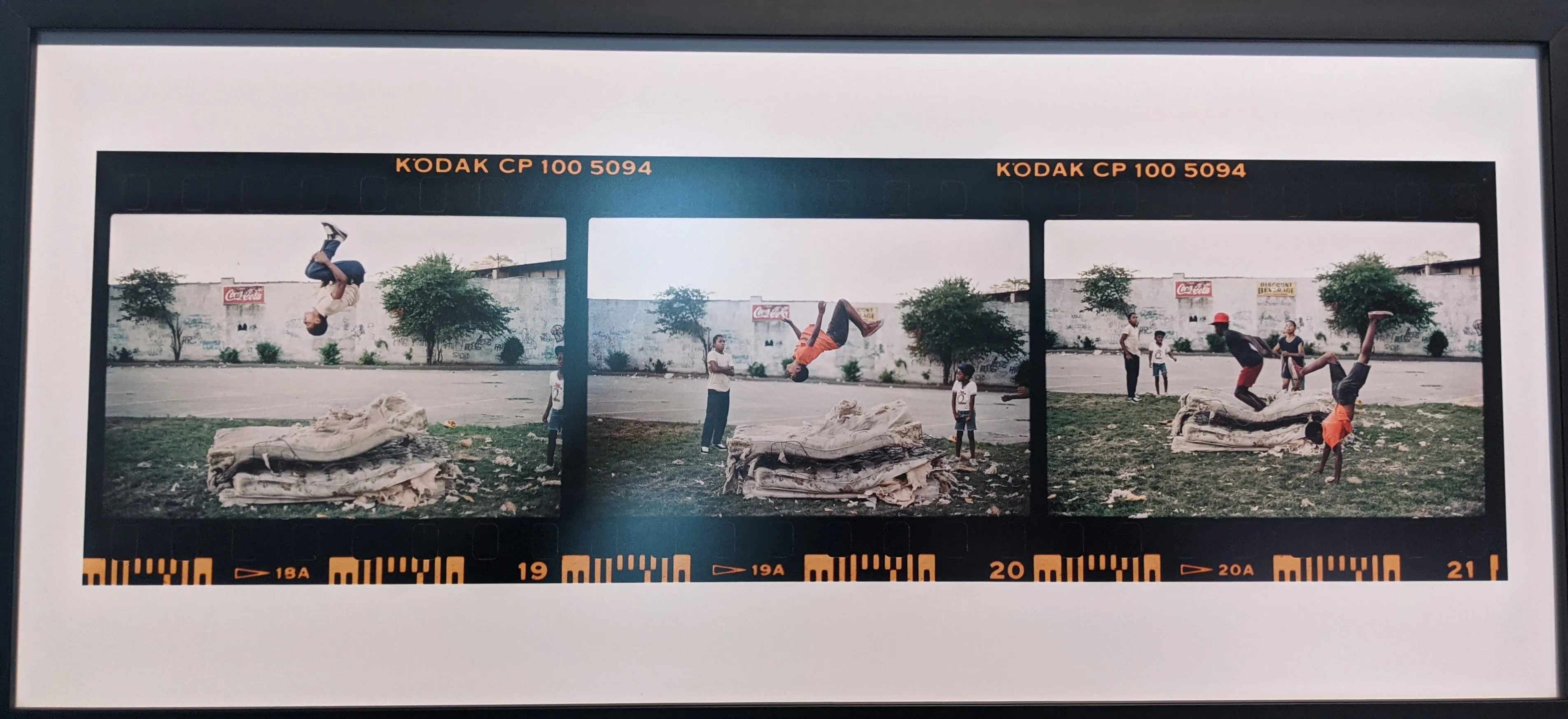

One of the first things I saw when I entered the exhibit was the Undun album cover: a black-and-white photo of three kids, in which one is doing a backflip on top of tattered mattresses, with a crumbling building in the back.

That photo was taken from a series by Jamel Shabazz in Brooklyn in 1982 called "Flying High." Shabazz was known for his street portraits. It took him three frames to capture "Flying High" with his Canon AE-1 camera, which are all displayed in the "Contact High" exhibit. Like Undun, the photograph highlights the undissolving strength and beauty of inner-city youth who grew up under some of the harshest circumstances.

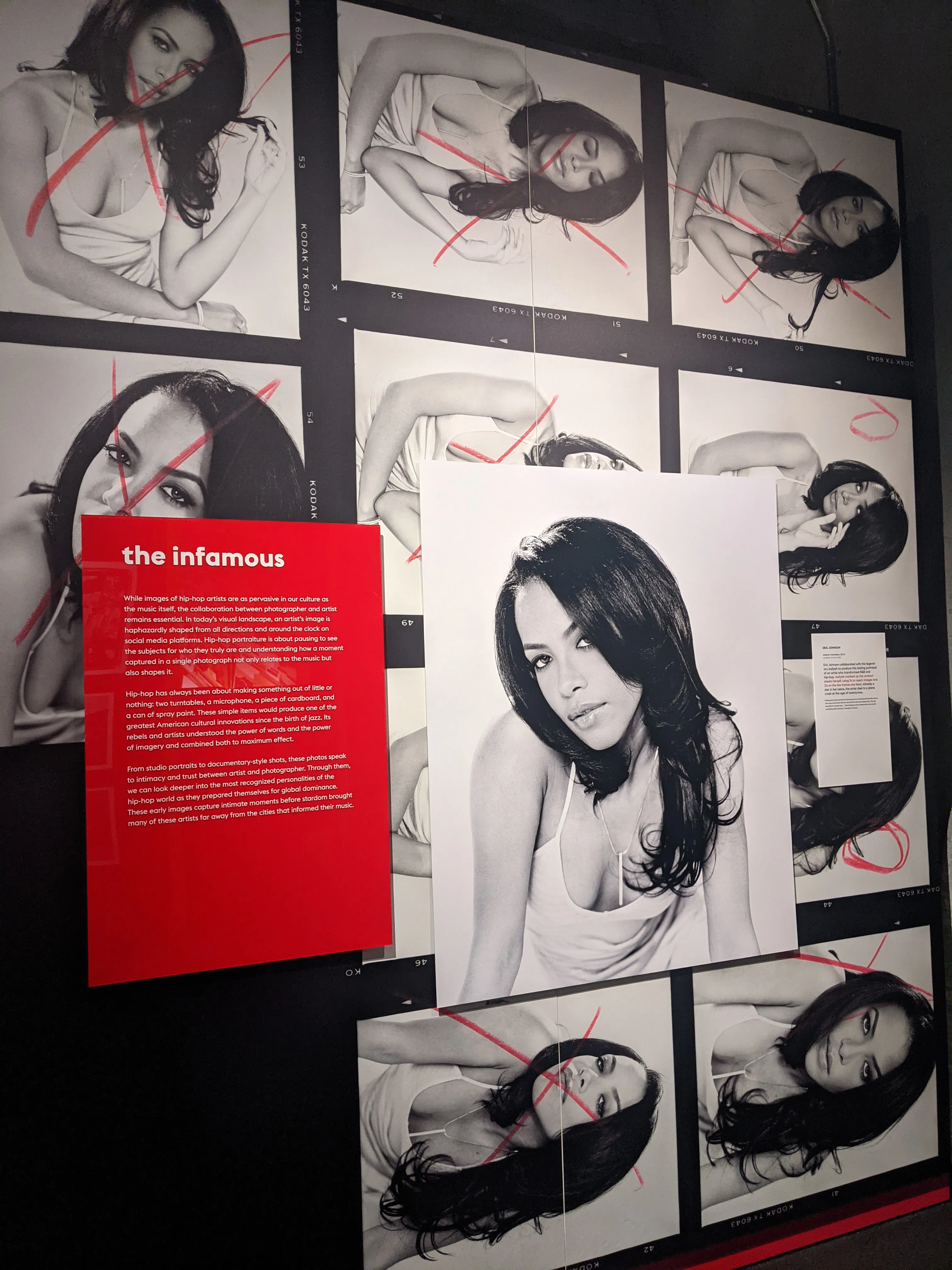

The most striking thing about this exhibit are the contact sheets, which are prints from rolls of used film. Many displayed are placed alongside some of the most iconic images of hip-hop artists. They allow one to look into the creative processes that took place between the subjects and the photographers. The increase in digital photography and social media has made these contact sheets rare these days.

A large black-and-white portrait of the young Aaliyah, taken in Manhattan in 2001 by Eric Johnson,, is displayed on one of the walls of the exhibit, with blown-up images of the contact sheets from the photo shoot behind her. Aaliyah became a star in her teens and was one of the first women to sing smooth and honeylike R&B vocals on top of hip-hop beats. Aaliyah marked the contact sheets herself, circling pictures she liked and crossing out those she didn't with a big X. (At the young age of 22, the star died in a plane crash.)

The MoPOP exhibit also includes one of the most recognized photographs in hip-hop history: Biggie Smalls' "King of New York" photo, taken by Barron Claiborne for a Rap Pages photo shoot. Biggie changed the genre forever with his deep voice, which exuded flowing wordplays and immaculate storytelling. Alongside that photo are contact sheets, which show Biggie smiling – something that was not common for the artist. In addition to the contact sheets, there is an original copy of Biggie on the cover of Rap Pages. Three days after the photo shoot, he was killed in a drive-by shooting in Los Angeles.

"I'm proud of the image. There are so many images of Black people, rappers or not, that you don't see in American culture," said Claiborne. "You rarely see them as regal. When you see something different, you embrace it. The fact that he died made the symbolism stronger. He had to die for that image to have that symbolism. The king sacrificed. But Biggie has the crown."

Another wall of "Contact High" features blown up portraits of more recent hip-hop artists. Tyler the Creator – a rapper who has implied in his lyrics that he is Gay, after years of homophobic songwriting – was pictured in a snapback, sticking his teeth out. A portrait of Kid Cudi wearing reading glasses and a beanie with his arms crossed is also on display, as is photograph of Queer icon Nicki Minaj dressed in tights and a bra serving food in a diner.

Not only does the exhibit include iconic photographs of male and female hip-hop legends and over 75 unedited contact sheets, but it also includes artifacts such as the Dapper Dan jacket that was made for Rakim and MF DOOM's legendary mask. Also featured are early rap-battle flyers, Tupac Shakur manuscripts, Flavor magazines, and costumes from The Notorious B.I.G. and Sha-Rock.

MoPOP's "Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop" exhibit, which opened on Oct. 16, will leave you speechless.

Starting on Oct. 25 the museum will require all attendees over the age of 12 to show proof of vaccination or a negative PCR COVID-19 test dated within 72 hours of the visit. To buy your tickets, visit https://www.mopop.org/visit/museum-tickets.